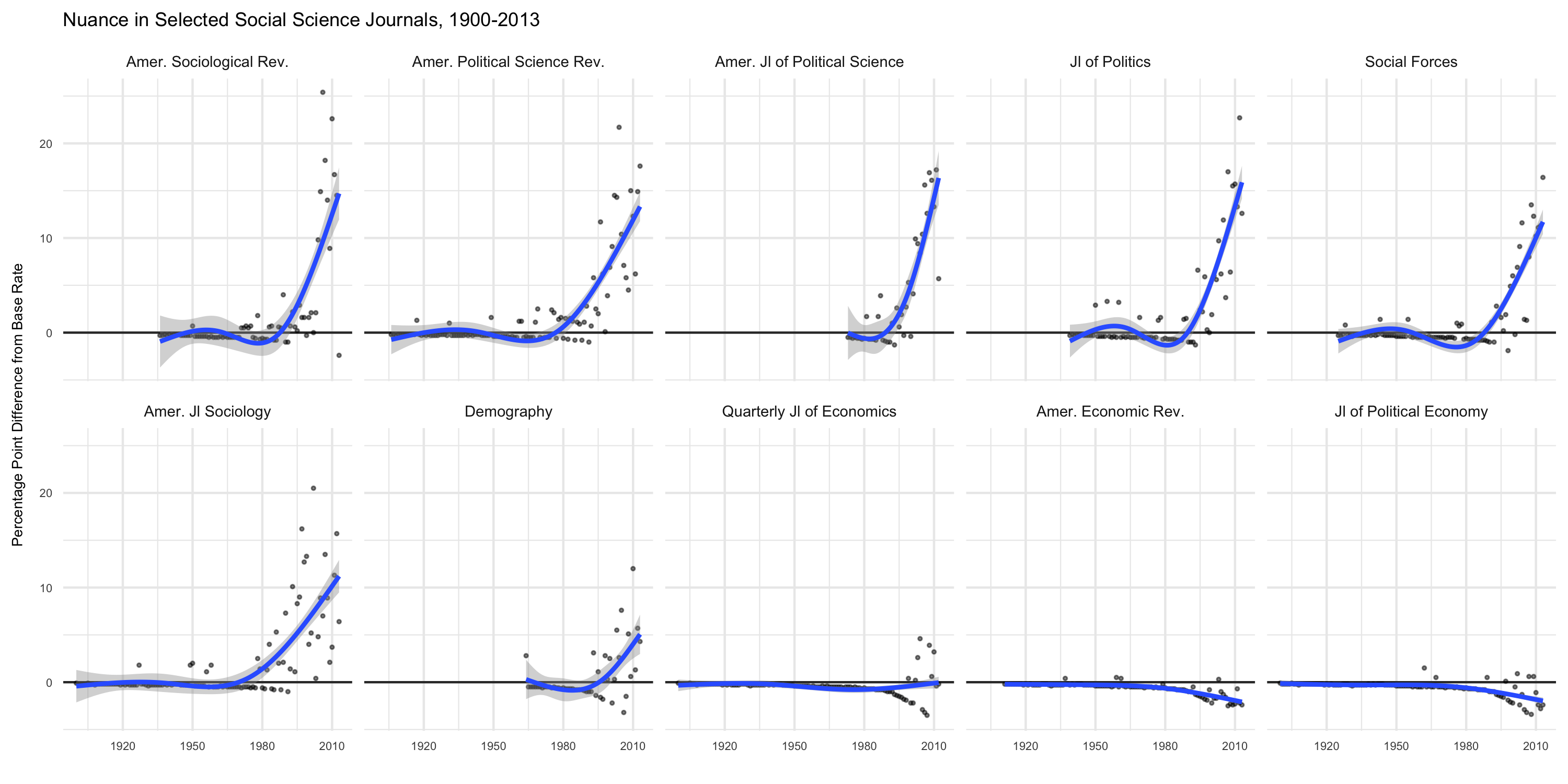

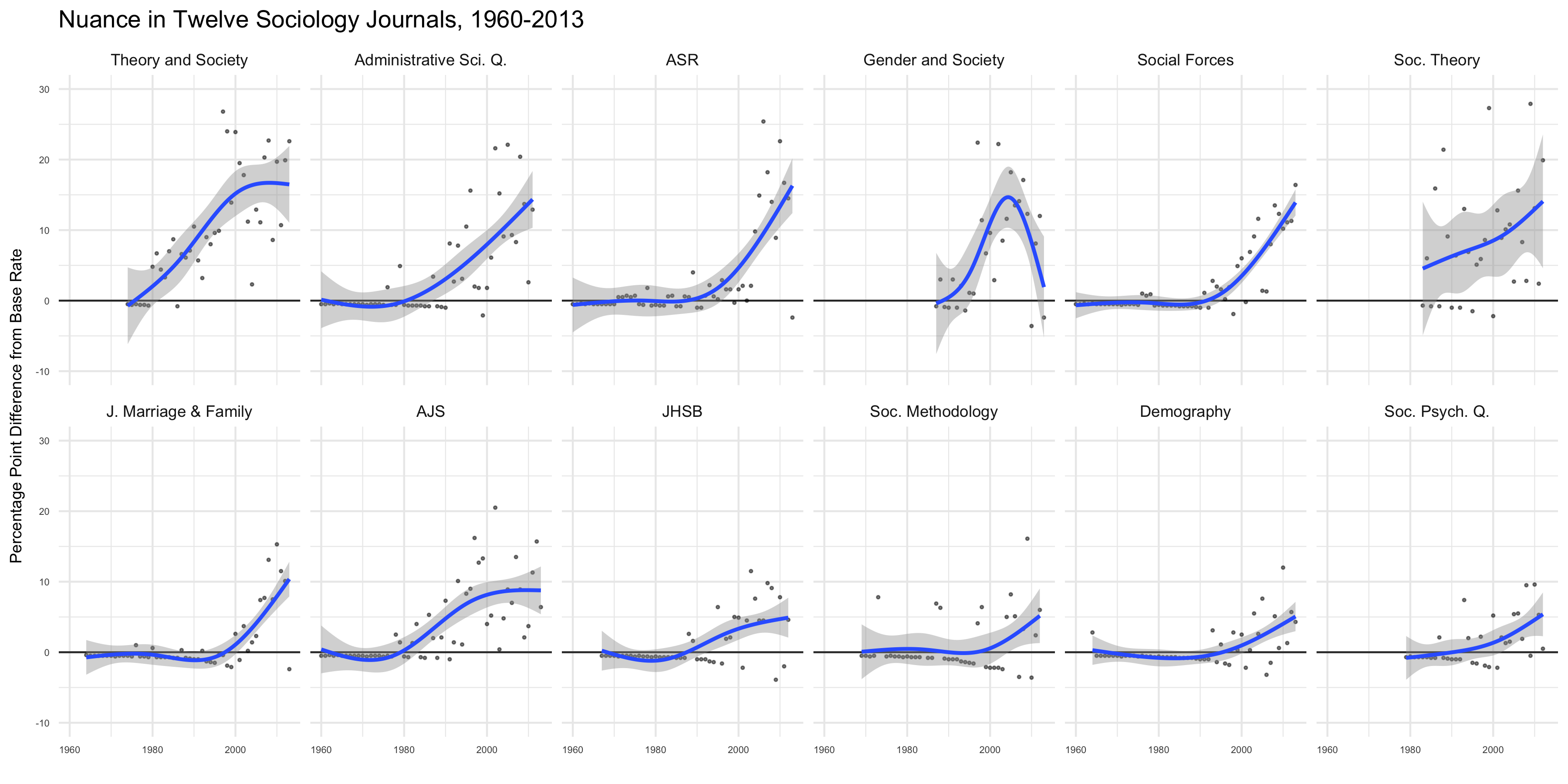

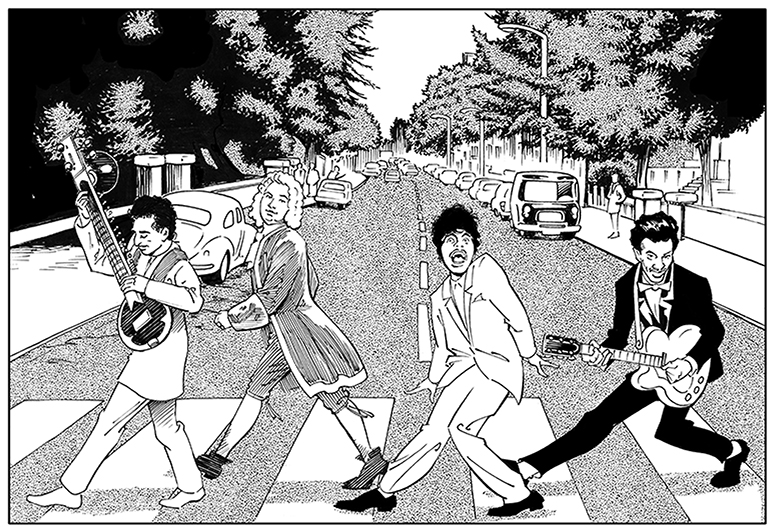

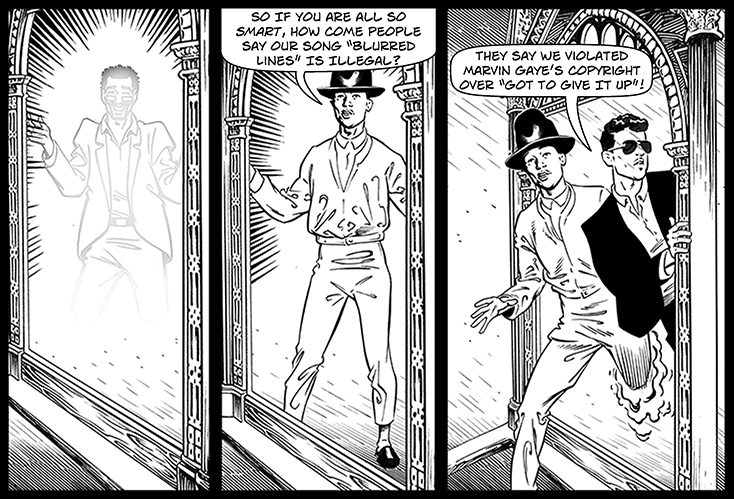

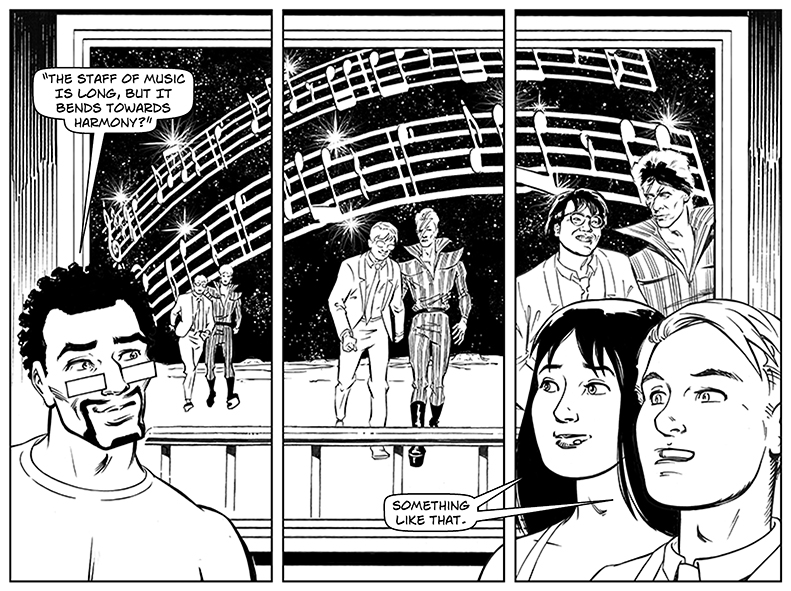

“To those who think that mash-ups and sampling started with YouTube or a DJ’s turntables, it might be shocking to find that musicians have been borrowing—extensively borrowing, consciously and unconsciously—from each other since music itself began,” write James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins, two superhero academics have taken on the subject of music and creativity in a new graphic novel. Meticulously researched and incredibly entertaining, the book explores 2,000 years of musical history, from Plato’s admonition that “musical innovation is full of danger to the whole state” to the recent “Blurred Lines” case – and everything in between.

Theft! A History of Music is the newest comic from Jenkins and Boyle, the team behind the 2006 fair use comic Bound by Law. Theft was written in collaboration with the late illustrator and academic Keith Aoki; Boyle and Jenkins developed the graphic designs that were illustrated and inked by Ian Akin and Brian Garvey. The book is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 and is available on the website of the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain.

Theft! A History of Music is the newest comic from Jenkins and Boyle, the team behind the 2006 fair use comic Bound by Law. Theft was written in collaboration with the late illustrator and academic Keith Aoki; Boyle and Jenkins developed the graphic designs that were illustrated and inked by Ian Akin and Brian Garvey. The book is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 and is available on the website of the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain.

In the book’s afterword, you write that you thought you were “done with comic books.” Why this one, and why now? How did the process of writing this book, which took ten years, differ from your previous comic, “Bound by Law?” Why did you decide to take on music as your next subject?

Bound By Law had success far beyond our expectations because it met a need – it explained fair use to a generation of creators and reusers of culture who found the language of copyright law mystifying and felt thwarted by the “permissions culture” of today, which presumes that permissions and fees must be attached to even the tiniest piece of creative culture.

We thought the same was true of music – particularly the permissions culture point. But when we came to write the book we saw that it had to roam much further, through the history of attempts to regulate musical borrowing – whether on grounds of philosophy, religion, race, or property rights. We saw common themes in all of those, common relationships between technology, incentives, law and the fire of sympathetic inspiration, which is impatient with barriers – whether it was a generation of white teenagers being inspired by African American rhythm and blues, or a church composer taking from the songs of the troubadours. As for the ten years it took us to finish, that gets to the pledge we made to our dear departed colleague, Keith Aoki.

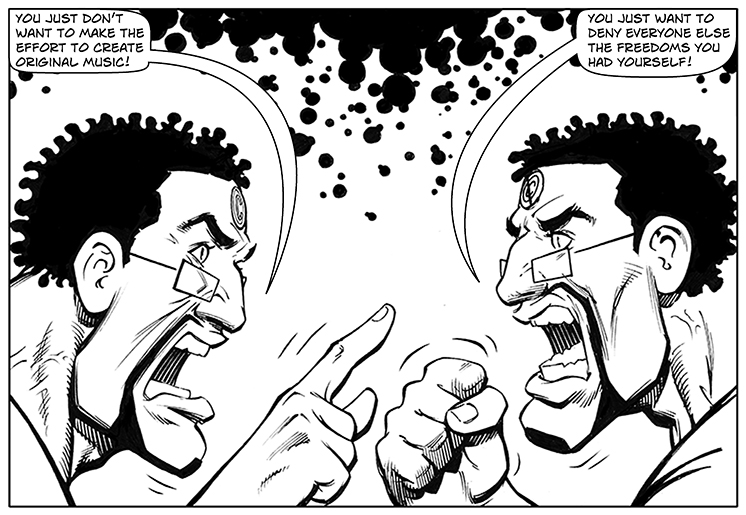

In some “superhero” type scenes, your protagonists struggle with the push and pull between power and control vs freedom, with alter-egos employed to demonstrate the impossibility of the decision. How do you, as academics and authors, reconcile the tension between these two forces?

We don’t think that the forces can ever be reconciled once and for all; they are dynamic tensions that actually drive the art. The important thing is to understand that this is a dynamic balance, not a simple equation where more control means more incentives and thus more art.

Jamie still remembers the first conversations with Larry Lessig, Hal Abelson and others about why we needed Creative Commons – we asked the Copyright office how creators could choose to share, to make their material freely available for others to use and build upon. Their answer was “we don’t provide that service.” That is missing a key part of the cultural dynamic – the fact that culture needs raw material on which to build. Creative Commons tried to deal with one aspect of that, namely the sharing commons. But we understood very well that some of that raw material needs to be there because law doesn’t reach it in the first place. For example, E=MC2 or the alphabet aren’t “owned” and if they were you would get less creativity, not more. Yet that does not mean freedom is always the answer. We want artists and composers to have rights over their work and to receive the compensation and attribution they richly deserve. That is in their, and our, interests. But it is also in their interests to have the freedoms to build on the past in interstitial ways that prior musical generations took for granted!

Something I found particularly compelling about the book is the complicated nature of many of the artists’ copyright disputes juxtaposed with lighthearted illustrations and narrative. For example, you discuss a number of surprising stories from the 20th Century, like the clampdown on the kind of sampling in early Public Enemy (the court decision announcing “get a license or do not sample”) or the case finding George Harrison liable for “subconscious” copying. You also include more distant history about Bach, Gutenberg, and even Plato in ways that are easy to understand and often irreverent. What was it like to turn court cases and history into comics? How did you employ storytelling tropes to craft a narrative out of 2000 years of scholarship and history?

Each domain of creativity – from music to comics – has its own dynamics. As academics, fond of long, carefully constructed arguments, we found it a wonderful challenge to fit complex and multifaceted ideas into a comic panel, a picture and a short speech bubble! But designing each of those panels was what made the art so truly satisfying – it was a rush, a creative high. As for law, it can be the subject of both art and humour – look at what Shakespeare and Dickens do with it! The question for us here was whether we could be technically faithful to the details and nuances – this is academic research with references behind every assertion, but it is also an attempt to capture a “conversation” that has been going on for hundreds of years, and do so fairly.

Even a casual reader will notice that the book is well researched. How did you do the research? How did you decide on the narrative structure, from the invention of notation to “Blurred Lines?” What primary sources did you draw on, and how did you do it collaboratively?

Again, there is so much to tell. We worked with composers and musicologists – our colleague, Dr. Anthony Kelley of the Duke music department bears much of the credit there. We taught classes made up of half law students and half composers and asked each group to explain the lines that the other group drew around “allowed” and “forbidden” creativity. We scoured the great books about musical history and borrowing – there are many. We drew on the legal scholars who have touched on this debate – Mike Carroll, another person on the CC founding board has written several of the most important law review articles on the subject. And above all, we listened to how music has been influenced and changed over time.

As for the structure, it emerged out of the chaos of our desire to tell the story and our panic that we wouldn’t be able to do so in a way that showed how fascinating it is. The readers of the book will be the best judge of whether we succeeded.

The book ends with a question – what will music production and rights look like going forward? How will musicians find their way in the 21st century? What do you think is the future of music?

We see several possible futures. Frankly, if we go on our current path – with the permissions culture extending legal claims to the atomic level of musical creativity – then we think that the future will be poorly served. We say in the book that we wouldn’t have got jazz, rock and roll, soul or the blues if we had used the rules we have today. Those musical forms would simply have been made impossible. It is a horrifying thought to think of that dynamic denying us the next great musical form. But we also see a reaction against that cultural sclerosis. We wanted this book to provide the raw material, the balanced information, that helps us decide as a culture which line we wish to go down.

Watch a three minute video about the book below:

The post The staff of music is long, but it bends towards harmony: An interview with the authors of Theft! A History of Music appeared first on Creative Commons.